Soft Matter Hacker Talks |

|

|---|

Home - Research - Publications - Blog - Talks - About

Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn | Google Scholar | Scopus | ResearchGate | UNSW | YouTube

Thanks for giving me the time to talk about this today. This work was the focus of a really talented post-doc, Vincent Poulichet, who had the task of adapting some of my group’s past work for new applications in the inhaled drug delivery space. The work was a collaboration between my group and Daniela Traini’s group at U. Sydney and the Woolcock Institute, and was funded by our shared ARC Discovery Grant that ended last year.

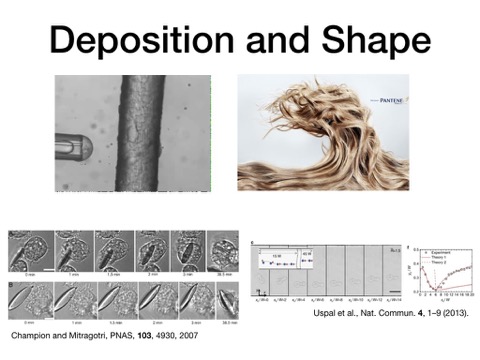

Today I want to talk about the process of depositing particles onto biological surfaces and how to engineer it better. In consumer products, we need to deposit emulsion droplets of silicone, the active softening agent in shampoos and laundry detergents, onto hair or fabric fibers.These are the most expensive ingredients in these products, but they deposit at a terribly low efficiency, ~1%, meaning most of the material is wasted. I was really pleased to hear from our Plenary speaker this morning, Samir Mitragotri, that a similarly low level of delivery efficiency plagues many types of drugs being delivered. As a result, even small increases are then significant from a performance and sustainability perspective. Two key contributions gave us hope for our own delivery problem. Samir’s group showed that even biological processes can be hacked by purely physical attributes, like particle aspect ratio. Pat Doyle’s group then showed that shape can be used to alter particle flow direction to enhance deposition. All we then needed was a way to make emulsion droplets, the most spherical thing you can find, adopt and retain non-spherical shapes.

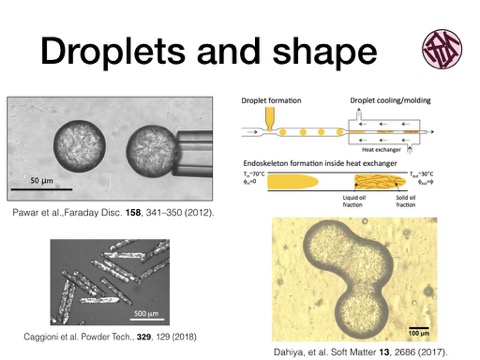

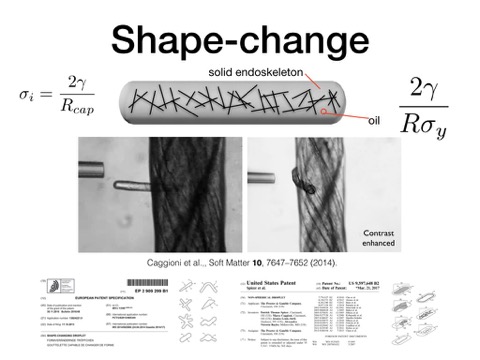

Drops can hold a non-spherical shape if something offsets the interfacial tension trying to force them into a spherical shape. We showed that adding elasticity to the droplet can do just this, here the droplets are an oil permeating a colloidal gel of waxy solids. The resulting viscoelastic drops are then able to retain a liquid surface for wetting targets, and their shape stability is designed by balancing the droplet yield stress with its interfacial tension. You can see these drops have the ability to hold a shape after their coalescence arrests. Shapes can then be molded into rods, for example by microfluidic means. Because they retain their liquid properties, they can undergo shape changes as a result of surface energy driving forces, as we see here for a third droplet added to an existing pair, that is then rearranged into a more compact shape automatically.

A simple force balance shows how these shapes are stable, with droplet yield stress elasticity offsetting interfacial tension. The equation also shows this balance can be disturbed by changing the key variables. This offers a significant benefit Rinsing, as done for all consumer product use, increases tension and triggers collapse of already deposited droplets, while heating reduces yield stress and crushed the droplets by interfacial tension.The performance enhancement of deposition, and retention, is ~30%, so the work was patented in US and Europe and forms the basis for your Pantene shampoo now.

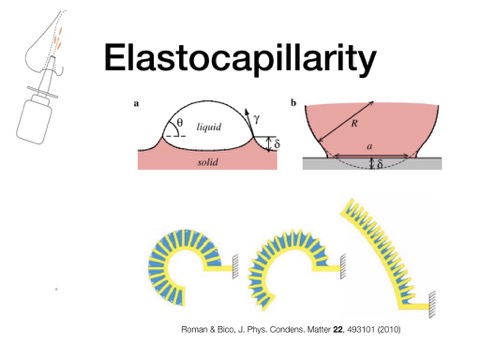

Around that time, I left P&G and started at UNSW, and Daniela Traini and Paul Young had the idea to adapt these drops for use as inhale-able particles. While shape change and retention is valuable, requiring an external trigger is not helpful in the nose or lungs. We needed a way to make these particles smarter to be able to sense and respond to their environment without an external trigger. We got an ARC Discovery grant to do this work, one focus was a mechanism nature uses to drive response to a local environment: elastocapillarity. Here fluid capillary forces, like surface tension, act in concert with the elastic response of solid-like materials to drive movement. This is seen when a liquid drop is on an elastic solid, and when adhesion pulls soft solids together, and is used to move leaves, fold pollen, and shoot seeds surprising distances.

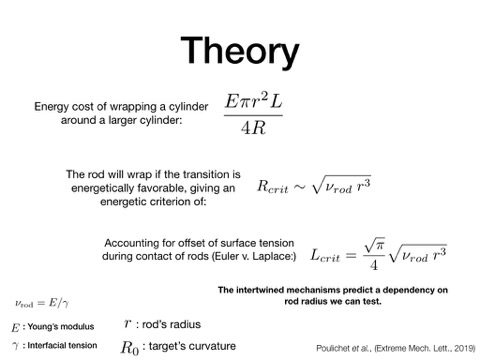

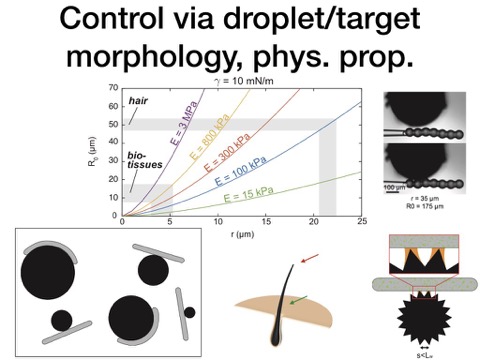

What Vincent realized was that he could adapt these models to assess and design our system so that it wraps around a surface it is touching purely as a result of elastocapillary response. Specifically, the rods respond to the curvature of the surface they touch and only wrap around surfaces below a threshold curvature because of the force exerted by the liquid meniscus of the droplet. Two approaches can be used to describe what might happen in these cases. The first is energetic, comparing the energy change upon wrapping a smaller cylinder with radius r around a larger cylindrical target with radius R. If favorable, wrapping is preferred to simply wetting at a contact point. A more realistic, but complex, description accounts for the Laplace pressure exerted by the interfacial tension and the partial stabilizing action of the Euler buckling criterion. Both approaches provide a criterion for the threshold target radius above which wrapping will occur, and that it scales with the rod-shaped droplet radius to the power of 3/2.

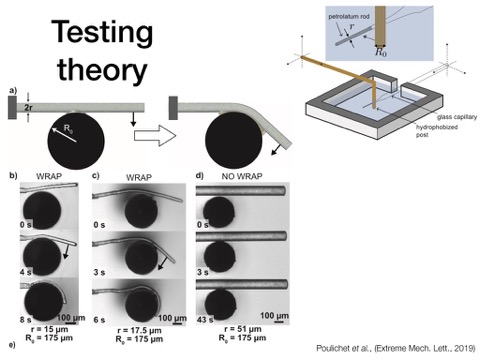

We test the theory using a small, surface-treated rod target whose radius we can vary by using different-sized glass capillaries. Extruding structured rod droplets of different radii and bringing them into wetting contact with the target allows us to directly observe whether wrapping occurs, or not, and document the dimensions. As the example images show, a larger relative target radius induces wrapping in two different rod droplet systems, but as the radii approach the same magnitude wrapping is not possible.

Plotting all the data obtained from the microscopic experiments and plotting the predicted scaling relationship shows the boundary between wrapping and non-wrapping follows the 3/2 scaling quite well. A fit to the data yields a ratio of elastic modulus, E, to interfacial tension, \gamma, that agrees well with the system parameters. Despite its simplicity, we find the theory to be a useful description of the wrapping and retention behavior for structured droplets.

The theory then allows is to develop a design guide for different target tissues or structures. We can then create application-specific materials. An example is the targeting of anti-dandruff actives in shampoo to the base of a hair, where curvature is lower than at the thinner upper end of the hair shaft. The base of the hair shaft is where pesky dandruff-causing fungus tend to reside, near the surface of the follicle.

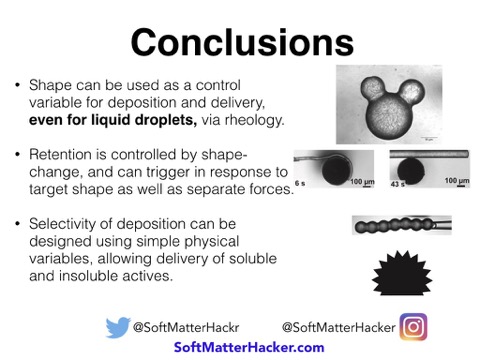

So, we find that shape can be designed and controlled in small liquid droplets with a range comparable to solid particles, all by careful design of the fluid rheology. Shape-change can be applied using external triggers, but a form of sensing can be exhibited by the shaped droplets, via elastocapillarity, in response to local curvature of a target. This simple, but smart, effect enables selectivity in droplet deposition and retention, allowing the enhanced delivery to be applied in systems where external triggers can’t be practicially or safely applied. Best of all, this is a purely physical effect: if you have the right rheology and wetting it can be achieved. And these things are easy to design into different types of systems.